Server -> Client streaming using Server-Sent Events (SSE)

In the previous tutorial we used query strings to send arguments to the server to specify options or parameters for how a function should run. While passing such arguments is very useful, this kind of communication is very limited. It can only happen at the time when the request is sent, and can only go one way, from the client to the server. What if we needed to send information the other way - from the server back to the client? Well we are already doing this through the return at the end of the functions attached to our routes, but this can only happen once at the end of the request. What if we wanted to send information at any time, even while a process was running? In our case this would be very useful for monitoring the activity of the backend server, particularly as we begin to develop more advanced processing code that could take some time to execute. In these cases it would be great if the server could communicate back to the client about which stage of the process it was on, and how much longer the process was expected to take.

In the past, sending information back from the server involved a large amount of setup, and used complicated technologies such as WebSocket to handle the communication. More recently, a new technology called Server-Sent Events (SSE) has been developed to simplify such communication within smaller applications. SSE allows the server to send back messages using simple HTTP responses, which can be picked up by the client’s web browser and presented back to the user. Most modern browsers support SSE, as does Flask, so we will use it to develop a communications channel from our server to the client to get real-time feedback on the processes being run.

Switch to the 04-streaming branch in the ‘week-4’ repository. This branch should have all the code we’ve written until now, and provides a good base for us to set up the SSE communication. SSE works by creating an ‘EventSource’ object in JavaScript on the client side which listens for communication events coming from the backend server. To make this work the ‘EventSource’ object is connected to a special function in the Python server code which gathers messages generated by the server and sends them as typical HTTP responses back to the client. For more information on the SSE protocol, you can consult this reference.

To enable this communication we will have to make a few small edits to both our app.py Python server code, as well as our index.html client code. Let’s start with the app.py code and outline how the messages will be sent from the server. To allow our server to send response messages to the client we need to first import the ‘Response’ module from the Flask library. Open the app.py file, and under the other flask imports, add the line:

from flask import Response

This module will allow us to send HTTP formatted responses to the client. However, before we send messages back to the client, we need to store them locally in a special type of list. This list will store new messages as they are created on the server, and a special communication function will be able to access them in the order they were created and send them back to the client. These kinds of data structures (often referred to as ‘buffers’) are crucial when dealing with asynchronous communication, since they ensure that your data is stored locally until it is sent over a network. Without these data structures data could easily get lost due to communication delays or errors, which can easily happen due to network difficulties or other connection issues.

To create this buffer, we will use a special Python data structure called a Queue, which is basically a list with special functions to deal with how data enters into and is accessed from the list. In a Queue, data is put into the list with the .put() method, which places the new piece of data at the back of the list. Then, the .get() method pulls one piece of data from the front of the list, accessing the data in the order that it was placed in the list. You can think of this as a queue of people lining up to get tickets. As people enter the queue from the back, the line grows, and the first person in line is the first to get tickets. This data structure is very useful because the .get() method returns the data at the front of the list while simultaneously removing it from the queue, which makes managing the queue easier. The Queue is one of two basic extended list structures often used in computer programming. The other one is a Stack, which implements the same .put() and .get() methods, but accesses data in reverse order, with the first item accessed being the last item placed ‘on top of’ the stack.

In order to use Python’s Queue object, we must first import it into our code. Below the other imports at the top of the app.py file add the line:

from Queue import Queue

This will import the Queue object from the Queue library, allowing us to use it in our code. Now, let’s make a new queue to store our messages. After the line app = Flask(__name__), add the line:

q = Queue()

This creates a new instance of the Queue object and stores it in a variable called ‘q’. Now we can add messages to the queue by using its .put() method, and access items from it using its .get() method.

Next, let’s create a function which will stream the contents of our queue to the client. On the next line, add the following lines of code:

def event_stream():

while True:

result = q.get()

yield 'data: %s\n\n' % str(result)

This code specifies a new function called ‘event_stream’ which constantly checks the contents of the ‘q’ queue and sends any new messages it finds back to the client. Notice that we are using the while True: loop, which in most other cases would be a very bad idea, since it would cause Python to enter an infinite loop and crash as a result. In this case, by using the ‘yield’ structure instead of a ‘return’, we are creating an asynchronous ‘generator function’ which returns only one value at a time, only when it is requested to do so.

This is a more advanced type of programming which deals with asynchronous events and communication, so don’t worry if you don’t understand it completely. In a basic sense, this function is only establishing a way for the client to constantly get updates about the messages in the ‘q’ object. After we tie this function to an ‘EventSource’ object on the client side, this function will constantly monitor the contents of our queue and send out any new data it finds in the proper format. This format is specified in the concatenated string after the ‘yield’ key word. We send the data back starting with the string ‘data: ‘ and ending with two line end markers (‘the \n symbols’). The %s is a wildcard which lets us concatenate strings in a more clean way, similar to how we used {} and the .format() method in a previous tutorial. You can see more examples and an explanation of formatting for standard SSE event streams here.

Next, let’s specify a new route on our server which will be accessed by the client’s ‘EventSource’ object, and will point this object to the ‘event_stream()’ function that it will use to get data from the queue. On the following lines, write:

@app.route('/eventSource/')

def sse_source():

return Response( event_stream(), mimetype='text/event-stream' )

This code creates a new route (similar to the routes we used before to get data from the server) called ‘/eventSource/’. When the client accesses this route, it will execute the following ‘sse_source()’ function. This function will return a basic Flask ‘Response’ object. Into this Response object we pass our ‘event_stream()’ generator function, which specifies the mechanism for how the messages are streamed. We also specify the type of stream we’re sending by passing mimetype='text/event-stream' to the second input.

If you find this code difficult to understand, don’t worry! The low-level concepts behind this kind of asynchronous communication are quite advanced, and a full in-depth explanation of them is beyond the scope of these tutorials. However, as long as you can understand the higher level goals and implement this basic structure, you should be able to implement this kind of communication to create useful features in the Web Stack. If you get stuck, you can always check the 05-assignment branch in the ‘week-4’ repository, which contains the final code for this set of tutorials.

The last thing we need to do in the app.py file is to implement the communication by ‘pushing’ some messages to the queue at appropriate times within our server process. These messages can be anything, but a great use for them is to provide feedback about the activities happening on the server, particularly during operations that might take a long time to execute. For example, you might send one message at the beginning of the process to let the user know the request has been received and the process has begun. Then, you can send another message at the end to let the user know the backend process is finished and to expect results in the client. You could also send intermittent messages to let the user know where the server is in the process, or how much longer the process is expected to take. In our case, let’s add a message right after the /getData/ route is accessed by the client. Find the line in the app.py file that says ‘def getData()’ and after it add the line:

q.put("starting data query...")

This message will be added to the queue when the client first asks for data from the server. With the asynchronous structure we set up earlier, the ‘event_stream()’ function should immediately pick up this change in the queue, and send this message as a ‘Response’ object back to the client. The great thing is that this happens asynchronously, at the same time that the rest of the data query is happening in the getData() function. Let’s finish by adding another message once the data is received, right before it gets sent back to the client. Find the line that says return json.dumps(output) and add the following line directly before it:

q.put('idle')

This adds another message which signals that the ‘/getData/’ operation is complete, and the server is now idle, waiting for further instructions. This completes the changes we need to make in the app.py file. Save the file and execute it within a Command Prompt or Canopy session to start the server, and leave it running in the background.

Next, let’s implement the SSE communication in the front end client code. We will do this by creating a new ‘EventSource’ object within our JavaScript code, which will access the ‘/eventSource/’ route on our server. This route will tie the ‘EventSource’ client object to the ‘event_stream()’ server function, which will send it messages from the queue.

Open the index.html file within the ‘/templates’ folder of the repository. Before we write any JavaScript code we first need to create a new HTML object which will display the current message from the server. Find the <form> </form> tags in the index.html file where we coded the checkbox and submit button elements in the previous tutorial. After the code for the button (right before the closing </form> tag), add the line:

<p>Status: <em id="message"></em></p>

This creates a new <p> paragraph object with the text “Status: “. After this we add another structure, <em>, which typically designates text which is emphasized (usually designated as italic). We give this <em> tag a unique id of “message” so that we can reference it later within the JavaScript code.

Next, let’s write some JavaScript code to create the ‘EventSource’ object which will listen for messages sent from the server and display the incoming message on the page. First we need to declare some variables. In the index.html file, right after the <script type="text/javascript"> line that starts the JavaScript code, add the following lines:

var eventOutputContainer = document.getElementById("message");

var eventSrc = new EventSource("/eventSource");

This creates two new variables. The ‘eventOutputContainer’ variable stores a reference to the <em> structure we created earlier, allowing us to change its text content based on incoming messages. The ‘eventSrc’ variable creates a new JavaScript ‘EventSource’ object which will listen to the messages coming from the server. Into the object declaration we pass the ‘/eventSource/’ route on our server, which tells the ‘EventSource’ object where it should get its messages. This route establishes the crucial link between the ‘EventSource’ object on the client side and the ‘event_stream()’ generator function on the server side which allows SSE communication to flow from the server to client. The last thing we need to do is handle the .onmessage() event of the ‘EventSource’ object, which is triggered whenever the object receives a message. On the following lines, add the code:

eventSrc.onmessage = function(e) {

console.log(e);

eventOutputContainer.innerHTML = e.data;

};

Here we are specifying what should happen when the ‘EventSource’ object that is stored in the ‘eventSrc’ variable receives an event and triggers its .onmessage() method. In this case we will use an anonymous function to put the message we receive in the temporary variable ‘e’. We will then log this data to the JavaScript console, which will help us to debug by showing the data we receive directly in the console. Finally, we will display the message on the website by referencing the ‘eventOutputContainer’ variable we linked earlier to the <em> container on our site, and setting its ‘innerHTML’ text content to the message we receive. With SSE, the actual data returned (and in our case stored in the ‘e’ variable), is an object of type ‘EventSource’. This object contains alot of information related to the message which in some cases could be useful. If you are curious you can investigate the data returned by going to the Console and finding where the data was logged. In our case we only want the actual text content of the message being sent, which we can access through the .data portion of the ‘e’ variable.

This completes the changes we need to make to the client side code in order to enable SSE communication between the server and client. One last thing we might want to do is to add some custom styling to the <em> tag to give our message text an even bolder appearance. In the <style> </style> section of the index.html document, add a new style rule:

em{

color: red;

font-weight: bold;

}

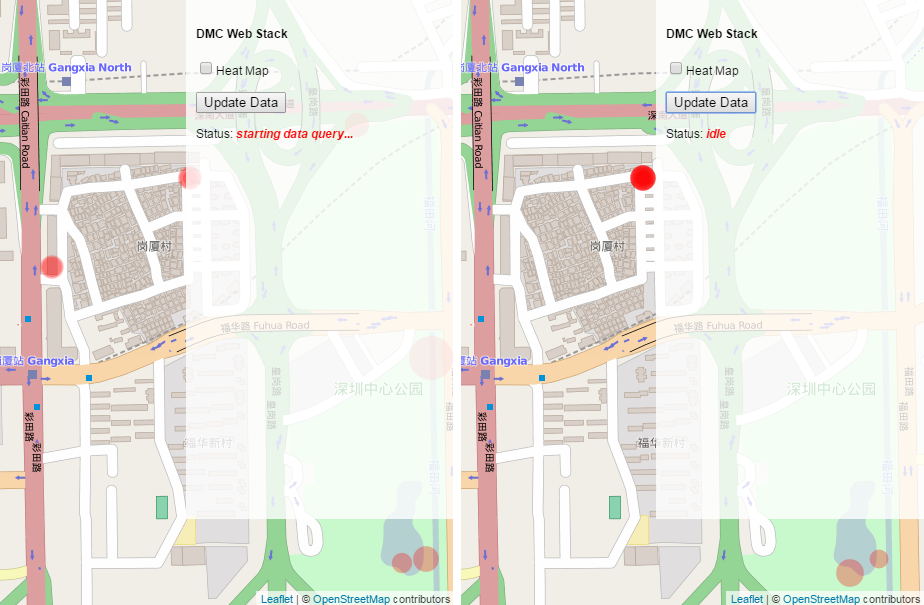

This will give the message text a red color and make it bold, in addition to the italics it gets by default. Save the file and navigate to localhost:5000 in your web browser. Now when you hit the ‘Update Data’ button, the text after “Status: “ should update with the current message coming from the server. Right after you click the button it should display “starting data query…” and as the data comes back it should update to “idle”.

As you can see, we did not need to add too much code to make this kind of communication possible. On the other hand, some of the low-level concepts behind this kind of asynchronous communication are quite complex, and are probably some of the most difficult concepts we will deal with in this course. So don’t be discouraged if you don’t understand exactly what all the code does. If you are able to implement this basic functionality and understand how to extend it for your own needs, you can use this kind of communication to add very useful feedback as we start to develop much more complex (and potentially time consuming) operations to the backend server.

This concludes our basic implementation of SSE communication, and the tutorials for this week. If you want to see another example of SSE communication using Flask, there is a great example here http://flask.pocoo.org/snippets/116/. This example is somewhat more advanced than what we have developed here, since it accommodates several clients creating individual connections to the same server at the same time. Although we do not need such functionality in our basic implementation, this is still a great example for exploring the features of SSE, and can be run independently within a single Python file.

We now have all of the basic client <-> server functionality of our Web Stack implemented, with a great framework for how the two parts of the stack can communicate and exchange information back and forth. For the remaining two weeks we will begin to develop more advanced processing functionality on the server side, including some basic examples of Machine Learning. We will also explore more advanced visualization examples on the client side using some of the dynamic features of D3. For now, switch to the 05-assignment branch in the ‘week-4’ repository. This branch contains the final version of the app.py and index.html files against which you can check your own work. It also contains some instructions within the comments which you should follow to test your new knowledge. Remember to submit a pull request with your changes before the next deadline.